Object Annex :: Attractive technology

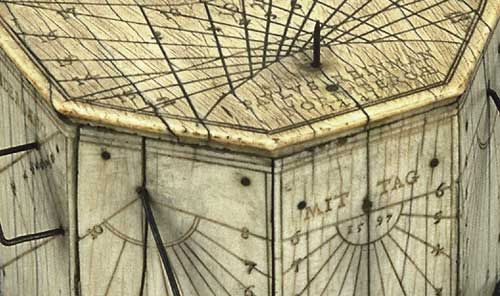

1597 Polyhedral Dial from the British Museum

1597 Polyhedral Dial from the British MuseumThis polyhedral dial is made from an octagonal block of wood, covered with layers of ivory. It has a pin gnomon dial on the top and on one of the faces, and unusual wire dials on the other seven faces.

Whilst Director de Plume is pre-occupied with her investigations into the mysterious goblin seen lurking around the museum, we obviously have to take up the slack. Someone has to get things done around here. The Director will, of course, receive an official memo. *1

Luckily we have, anyway, long wanted to draw attention to something close to our orderly hearts.

A database.

A database storing images and information about medieval and renaissance scientific instruments, to be more exact. Epact is an electronic catalogue of collections from the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford, the Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, Florence, the British Museum, London, and the Museum Boerhaave, Leiden. Together, these museums house the finest collections of early scientific instruments in the world.

There are armillary spheres, some 90 astrolabes to compare one with the others, dividers, gauges, measures, dials, quadrants, mining and surveying instruments and on and on. And they are all exquisite. There are over 520 instruments in all. Each instrument in the catalogue is described with the aid of one or more photographs and two levels of text: an overview text providing a short account of the most notable features of the instrument and a detailed text giving more technical and scholarly information.

Supporting material for the catalogue entries includes a thematic essay providing background information about the medieval and renaissance mathematical arts and sciences as well as a number of technical articles giving explanations of how the main different types of instrument operated. Short entries on all makers and places represented in Epact are supplemented by a glossary of technical terms found in the overview texts and a bibliography lists all references from the detailed texts. Terms from the makers and places indexes and the glossary are all cross-linked from individual catalogue entries.

In short, it’s authoritive, definitive and really very very interesting. And if it’s actually a little hard sometimes to find exactly what you’re looking for – there’s ample opportunity to wander off into fascinating byways and meandering thought associations.

For example: the fact that the past was obviously the habitat of cerebral giants. Nothing was easy then. Even the act of telling the time seemed to demand an advanced knowledge of astronomy and mathematics. At least on the evidence of a common time-telling devices from the 15th and 16th centuries. Take the astronomical ring dial. This timepiece comprised of three circles, one to be aligned with the equator, one with the meridian and the third to indicate right ascension and declination. We certainly can’t figure out how it works. Not a clue. We've thrown all our researchers at the problem. Though they make lovely shadows.

This 16th century example is of German make and can be physically found in the collection of Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza.

This 16th century example is of German make and can be physically found in the collection of Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza.A table sundial equally supposed that even children and the serving classes possessed a high level of calculating ability. Or did they have to call a mathematician in when they needed to know the time?

Left: 16th century, Polyhedral Dial made in Florence, Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza

Left: 16th century, Polyhedral Dial made in Florence, Istituto e Museo di Storia della ScienzaThis table sundial has eighteen decorated and painted faces. The hour lines are inscribed on every face in a different manner, corresponding to a different type of dial: horizontal, vertical, declining, etc. In use the instrument was oriented with the help of the compass.

Right: Polyhedral Dial, dated 1587. Florence, Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza

Polyhedral sundials of this kind, with finely decorated faces, are typical of the production of Stefano Buonsignori, an Olivetan friar, who was cosmographer to Francesco I de' Medici. This is richly coloured and also decorated with the coat of arms of the Medici dynasty. The upper cavity has a housing for a compass, which is now missing. Each face of the instrument carries a different type of sundial, complete with gnomon. The compass allowed the instrument to be correctly oriented towards the North. In this way the shadows of the gnomons projected onto the hour lines indicated the time.

Polyhedral sundials of this kind, with finely decorated faces, are typical of the production of Stefano Buonsignori, an Olivetan friar, who was cosmographer to Francesco I de' Medici. This is richly coloured and also decorated with the coat of arms of the Medici dynasty. The upper cavity has a housing for a compass, which is now missing. Each face of the instrument carries a different type of sundial, complete with gnomon. The compass allowed the instrument to be correctly oriented towards the North. In this way the shadows of the gnomons projected onto the hour lines indicated the time.

*1 And note to self – get busy organising the Steering Committee. We need a body to direct our complaints about senior management to.

Epact >>

Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, Florence >>

British Museum, London >>

Museum of the History of Science, Oxford>>

Museum Boerhaave, Leiden >>

3 Comments:

I strongly protest! I haven't been chasing around after that Snorri character at all. in fact I expect to hear any time now from the private I that I engaged. Hired, I must add, so that I would not be distracted from my duties to the Museum.

And, in point of fact, I have been risking life and limb chasing giant rare Straandbeast around the beaches of Holland.

And what have you done? ...Found a database! Well, excuse me if I'm underwhelmed.

Hey Thanks for sharing this valuable information . I will come back to your site and keep sharing this information

Best NINJA Blender

See it here

Click for more info

click this

Great Share such a helpful and informative content. It helped me a lot. Thanks for sharing informative content. Hoping to see more high quality article like this.

Check over here

Helpfull hints

More info

My latest blog

Post a Comment

<< Home