The 93rd plate from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur (1904), depicting organisms classified as Mycetozoa.

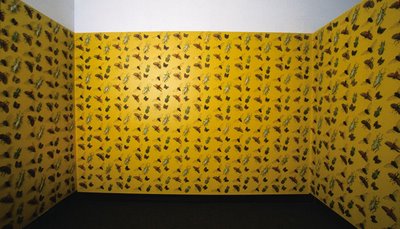

The 93rd plate from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur (1904), depicting organisms classified as Mycetozoa.In 1973 people in Dallas, Texas, were alarmed by an outbreak of strange large yellow growths on their lawns. When one of the big yellow blobs appeared on a telephone pole and began to spread, firefighters tried to subdue it with hoses. The mass grew. And began to moved up the pole. Most people thought it was an alien attacking their community.

Fortunately, a local university scientist identified the oozing slime as harmless F. septica. Yup, a slime mold.

Slime molds have it all… starting with their name. Not only does it start with the word ‘slime’ (closely related to dust, only with wet sliminess added!) but the ‘mold’ part is a lie. Fungi are molds… but slimes aren’t. Although people used to think they were. “Long classified together in the Myxomycophyta as part of the Fungi, slime "molds" are now known to be quite unrelated to the fungi.”

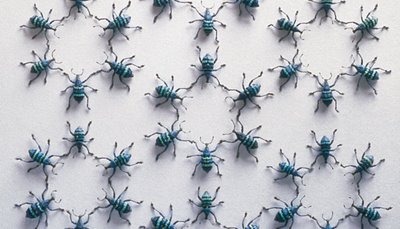

And then there is the way that slimes behave. They are the split personalities of the natural world. One minute they’re acting like a plant, doing nothing much just hanging around in rotting vegetation or dung… the next, when conditions become less convenient for them, they’re crawling together like animals, then fusing into a group form called a plasmodium. Moving at speeds up to 1 millimeter per hour (with an exceptional few moving as fast as 2 centimeters per minute), slime mold plasmodiums are slow-motion predators, usually locating bacteria or fungi to consume. They scavenge decaying organic material as well. As slime molds flow over and engulf their food, they ingest it. If an item turns out to be inedible, they eject it. Only to stop and turn back into a ‘flowering plant' for sporing… We

all know people who exhibit far less complex behaviors than this.

Slime molds apparently use chemical signals given off by food sources to sense which way to move. Researchers in Japan recently proved that Physarum polycephalum will consistently work out the shortest path between two piles of nutrients in a maze. (This I think, will have to be investigated more closely....)

Adding to the up-side, there’s the way that many slime molds look like vomit… And they come in many slimey colours including pink, orange, green and particoloured. Equally various are the common names for slime molds: wolf’s milk, yellow tinder blossom, Japanese lantern, bubble gum, spaghetti, red raspberry, chocolate tube, and tapioca. Many names suggest edibles, and, indeed, Indians in one area of Mexico scramble and fry Fuligo septica like eggs. They call their tidbit caca de luna or 'moon shit'. Some tropical slimes are bioluminescent and glow in the dark.

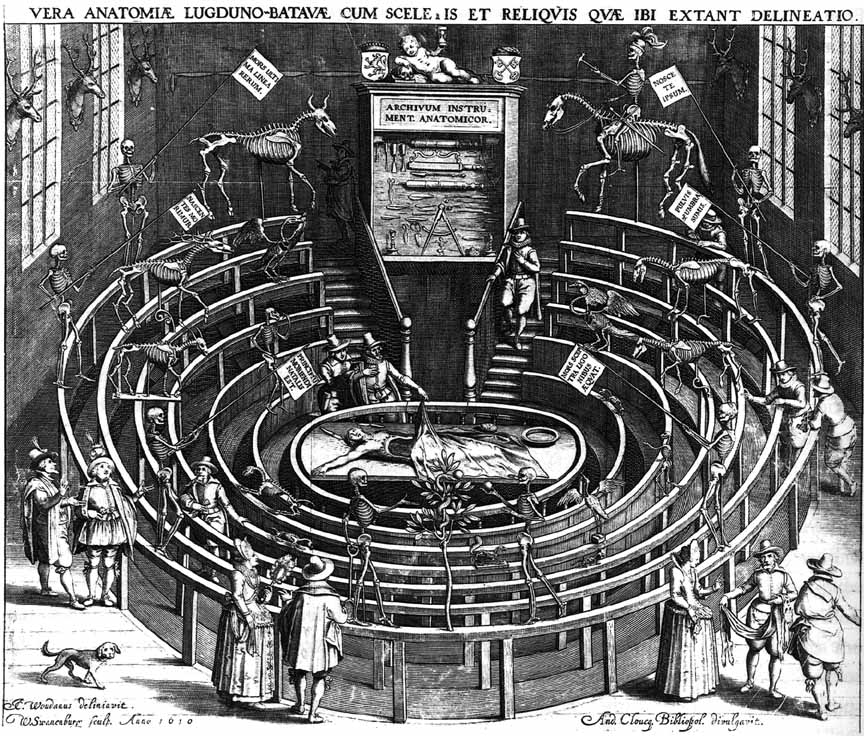

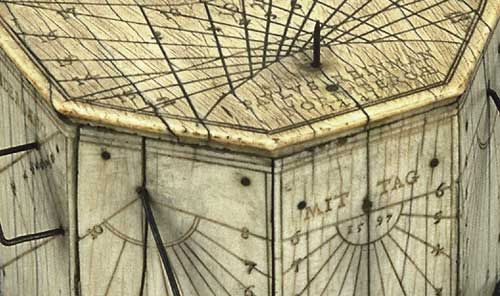

Most importantly, the 19th century scientific illustrator, Ernst Haekel, produced startlingly beautiful pictures of various slime molds for his 1904 book Kunstformen der Natur (Artforms of Nature). For more than a century, naturalists have cataloged slime molds in drawings, herbariums, and collections of cultured specimens. In Meiji-era (1868—1912) Japan, botanist Minakata Kusagusu was so determined to grow slime molds in his container garden that he trained cats to keep slime-mold-eating slugs out of his extensive collection.

And the fun doesn't stop there! In the early 16th century the Dutch artist Hieronymus Bosch depicted an estimated 22 species in The Garden of Earthly Delights. More recently slimes were included in the Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual and so are now staple in many fantasy role-playing games and computer games. These are truly lifeforms for all occasions...

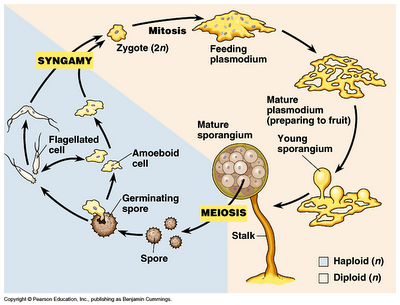

There are three main groups of slime molds. They do not, however, form a clade. Lucky really. All slimes, no matter what group, have a similar life-cycle.

The groups are:

1. Plasmodial slime molds are basically enormous single cells with thousands of nuclei. They are formed when individual flagellated cells swarm together and fuse. The result is one large bag of cytoplasm with many diploid nuclei. These "giant cells" have been extremely useful in studies of cytoplasmic streaming (the movement of cell contents) because it is possible to see this happening even under relatively low magnification. In addition, the large size of the slime mold "cell" makes them easier to manipulate than most cells.

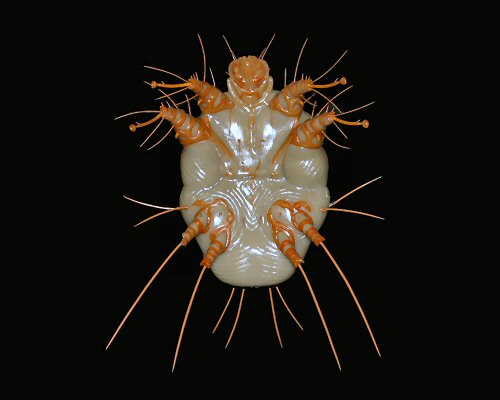

Slimy plasmodium of Fuligo septica the color of peanut butter. This creeping fungus moves very slowly in amoeboid fashion. A number of descriptive terms have been applied to this slime, including 'vomit slime mold' and 'dog vomit slime mold.' Photo by WP Armstrong

Slimy plasmodium of Fuligo septica the color of peanut butter. This creeping fungus moves very slowly in amoeboid fashion. A number of descriptive terms have been applied to this slime, including 'vomit slime mold' and 'dog vomit slime mold.' Photo by WP Armstrong

A second group, the cellular slime molds, spend most of their lives as separate single-celled amoeboid protists, but upon the release of a chemical signal, the individual cells aggregate into a great swarm. Cellular slime molds are thus of great interest to cell and developmental biologists, because they provide a comparatively simple and easily manipulated system for understanding how cells interact to generate a multicellular organism. There are two groups of cellular slime molds, the Dictyostelida and the Acrasida, which may not be closely related to each other.

A third group, the Labyrinthulomycota or slime nets, are also called "slime molds", but appear to be more closely related to the Chromista, and not relatives of the other "slime mold" groups.

Physarum Photo from Introduction to the Slime Molds and by Tom Volk.

Physarum Photo from Introduction to the Slime Molds and by Tom Volk.

Slime Mold Photos page by WP Armstrong >>

Wikipedia slime mould entry >>

Introduction to the Slime Molds >>

PhysarumPlus

An Internet Resource for Students of Physarum polycephalum and Other Acellular Slime Molds This includes links to movies, picture galleries and even an ode to this slime. >>

Some lovely pics of slimes : photographs by Stephen Sharnoff >>

The Elegance of Slime Molds >>

Slime Molds on Flickr

taka_itaha, a Dutch programmer with bio-interests and some other great funghi and nature sets, as well as one on slime-molds alone. >>

Myxomycetes-Slime Molds by GORGEous nature >>

Myxomycetes by myriorama >>

Slime Molds by Bistrosavage >>

Read more>>